The French general was aghast that his native allies massacred the enemy soldiers and settlers. The Maquis de Montcalm leaps to the defence of British parolees after the fall of Fort William Henry. The French were duly offered the Honours of War when they capitulated. It was also entirely common for opposing commanders to keep up a lively correspondence in between battles and during sieges. Impressed, he offered his apologies and sent her some West Indian Pineapples to make amends. While offering the services of his doctor to tend the French wounded, it had come to Amherst’s attention that Madame Drucourt had been firing the fort’s guns at him in retaliation for British shot striking her quarters. During the 1758 blockade of Louisbourg, General Geoffrey Amherst called several truces with the enemy commander, Chevalier de Drucourt. It did a general’s reputation no end of good if, during a long siege he displayed some sportsmanship. Yes, the objective of any general is to defeat the enemy, but that doesn’t mean you should be a boor about it.

(Image source: Tourism Nova Scotia) Be a Good Sport “We never fire first fire yourselves.” As it turned out, the French did let fly the first shots, after which the British closed advanced to within a few paces and delivered a devastating fusillade that killed or wounded as many as 700 enemy soldiers. “We are the English Guards, and we hope you will stand till we come up to you, and not swim the Scheldt as you did the Main at Dettingen,” he gibed, after which he invited the enemy to fire the first volley. “Gentlemen of the French Guards, fire,” he called. Upon closing to within musket range, elegantly dressed officers from both sides walked out in front of their men and an exchange of hat doffing occurred. As the coalition launched its attack against the French positions, the British 1st Foot Guards approached the enemy’s elite Gardes Françaises. On May 11, 1745, the Duke of Cumberland‘s allied army engaged that of the French under Marshal de Saxe at the Battle of Fontenoy.

(Image source: WikiCommons) Give Fair Warning French commanders tip their hats at the advancing British during the Battle of Fontenoy. After capturing Marshal Tallard at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704, the duke offered up his own coach for the enemy commander to recuperate while he continued the battle. Yet inconveniencing an enemy that had fallen into your hands was seen as bad form. Usually, their requests would be granted.Įven with a permission to travel, it could still be dangerous to move through hostile country. In fact, the Duke of Marlborough himself was once held up by enemy troops while making for home. In such cases, officers would apply to their foes for passes of safe conduct. Some would have to cross long distances and oftentimes travel through enemy territory. With the onset of autumn, armies would go into winter quarters and many officers would head home. How rude! (Image source: WikiCommons) Don’t Make It Personalĭuring the wars of 18th Century Europe, it was usual for armies to campaign in set seasons - usually from March to September. Consider the following: Despite receiving a safe passage from the French, the Duke of Marlborough was detained while travelling home through enemy territory. Military history writer Josh Proven of the site Adventures in Historyland explores some of these widely followed conventions, many of which may seem hard to believe to modern readers.

CHIVALRY CODE OF CONDUCT IN THE 1800S HOW TO

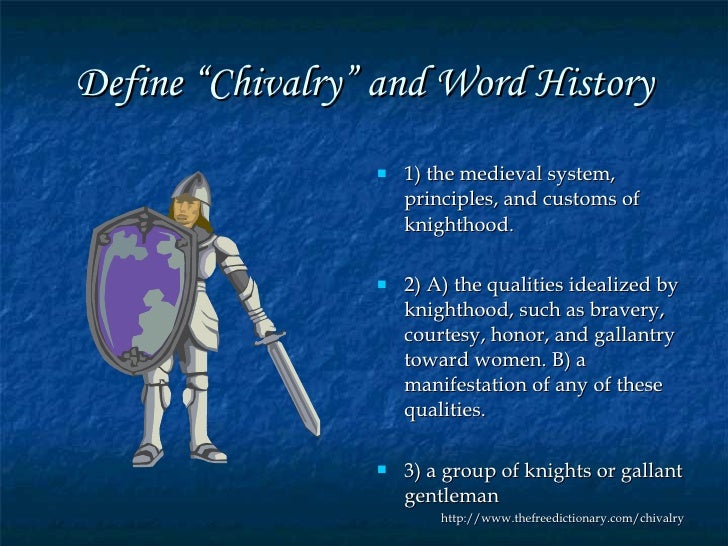

Later during the Medieval period, the Code of Chivalry established the ‘proper’ way for knights to behave both on and off the battlefield.īy the 18 th Century, a surprisingly comprehensive set of principles for commanders of armies emerged that instructed officers on how to fight like gentlemen. LAWS GOVERNING the conduct of armies in wartime are nothing new.Īs far back as the Old Testament, there have been attempts to regulate how combatants fight each other. (Image source: WikiCommons) “ Yes, the objective of any general is to defeat the enemy, but that doesn’t mean you should be a boor about it.” The famous fighting playwright was not the only genteel general on the 18th Century battlefield. “Gentleman” John Burgoyne surrenders at Saratoga.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)